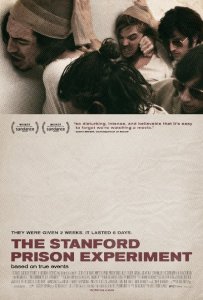

The Stanford Prison Experiment is Psychology 101. Introductory textbooks on the subject all make note of the events that took place at Stanford University in August of 1971, in which 18 college-aged participants and students simulated a prison environment as part of a psychological study by Philip Zimbardo. Half took shifts as ruthless, abusive guards, and the other half were punished, degraded, humiliated and malnourished as a part of their imprisonment. After just six days of an allotted two weeks, the results predictably did not end well. Students today look back on it as an example of a study gone horribly, ethically wrong, but also as an example of behavioral psychology.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is Psychology 101. Introductory textbooks on the subject all make note of the events that took place at Stanford University in August of 1971, in which 18 college-aged participants and students simulated a prison environment as part of a psychological study by Philip Zimbardo. Half took shifts as ruthless, abusive guards, and the other half were punished, degraded, humiliated and malnourished as a part of their imprisonment. After just six days of an allotted two weeks, the results predictably did not end well. Students today look back on it as an example of a study gone horribly, ethically wrong, but also as an example of behavioral psychology.

The film adaptation of this, also titled “The Stanford Prison Experiment” and directed by Kyle Patrick Alvarez, should also feel like essential psychology. The film makes abundantly clear in a string of darkly tense, even twistedly funny set pieces, just what happened here and how much a situation like this could affect these individual’s minds. What’s more, Alvarez leaves morality out of the equation. There’s notable ambiguity as to whether such an experiment should’ve ever been conducted, or if it actually produced real academic results and lessons on psychology.

But Alvarez misses an opportunity. “The Stanford Prison Experiment” is a horror story, a terrifically acted and fascinatingly lensed experiment of its own. But like the prison experiment itself, the horrors Alvarez subjects us to are mostly one-dimensional.

In the film, Zimbardo (Billy Crudup) shares the goal that the experiment is designed to test how an institution affects an individual’s behavior. With that broad of a thesis in mind, any experiment could be a success, and the Stanford Prison Experiment would qualify as a rousing one. But it’s hard to know what, if any, academic value any of this actually had.

All Alvarez makes clear is that it has an impact, and that when pressed and put under certain institutional circumstances, you begin to play the part. Prisoner 8612 (Ezra Miller) is the first to break. He’s sarcastic and non-conformist, and leads a successful revolt on the second day to barricade the doors to their cells so the guards can’t get in. But when he’s locked in the hole and has his rebellion ignored and subdued, he quickly begins to believe his imprisonment is real. On the other side of the coin, the prisoners lovingly dub one guard John Wayne (Michael Angarano) for how he dons a Strother Martin in “Cool Hand Luke” impression whenever he disappears behind those one-way aviator sunglasses.

Alvarez’s film is a series of these grim prison set pieces. One of the film’s first and best involves John Wayne making the prisoners recite their numbers in a role call. The camera tracks swiftly down the narrow hallway as each prisoner rattles off their rank, and Alvarez finds an awful lot of room for motion and leering framing without sacrificing the claustrophobic space of the actual set.

These re-imagined moments of history, all of them highly accurate to the available footage seen online, are so calculated and choreographed that the deliberate pacing calls attention to the abuse of the task-master guards. They’re arduous, torturous, talkative set pieces in which time evaporates and the scene becomes truly, psychologically draining.

That illusion disappears however when we step into Zimbardo’s real world. These scenes watching Zimbardo and his fellow colleagues observe the prisoners are far more procedural without feeling notably academic or insightful in terms of the film’s themes. Zimbardo begins to look less deranged and consumed and more clueless, as everyone ignores obvious signs of abuse and madness to the prisoners as though they were just flukes.

Alvarez isn’t interested in making a morality tale condemning Zimbardo or the students involved. This film isn’t a question of whether this study should or shouldn’t have happened. It doesn’t even contain the prison reform commentary that would eventually become part of Zimbardo’s later career. But if you’re not going to pose those questions about the academic value of such a study, why even include those scenes at all?

I imagine a Stanford Prison Experiment movie in which the Zimbardo character is completely absent, in which students get instructions from faceless figures, and the behind the scenes pulling of strings is as hidden to us as it is to the tormented and confused characters.

Alvarez really does manage to build a sense of terror and psychological dread. And the film is made up of an incredible who’s who of young actors, all of them standing out in individual set pieces, from Miller and Angarano to Tye Sheridan, Thomas Mann, Keir Gilchrist, Johnny Simmons, Nicholas Bruan, James Frecheville, Chris Sheffield and more.

But in just offering a historical document, Alvarez misses a chance to conduct his own psychological experience on his audience. “The Stanford Prison Experiment” is a powerful film, but perhaps not affecting.

3 stars

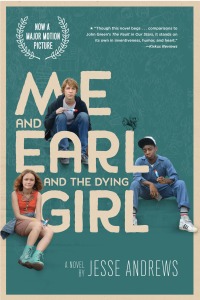

While independent cinema is traditionally any movie that’s independently financed, many newer film goers are first introduced to indies by what more experienced cinephiles have pejoratively labeled “The Sundance Movie”. They’re films like “Little Miss Sunshine”, “Juno”, “(500) Days of Summer”, “The Way Way Back”, and many more of varying quality. They’re not just movies that have premiered at Sundance; they’re quirky, irreverent, hipster, crowd-pleasing, charming, and to some degree, that horrible word best suited for Zooey Deschanel and Belle and Sebastian songs, “twee”.

While independent cinema is traditionally any movie that’s independently financed, many newer film goers are first introduced to indies by what more experienced cinephiles have pejoratively labeled “The Sundance Movie”. They’re films like “Little Miss Sunshine”, “Juno”, “(500) Days of Summer”, “The Way Way Back”, and many more of varying quality. They’re not just movies that have premiered at Sundance; they’re quirky, irreverent, hipster, crowd-pleasing, charming, and to some degree, that horrible word best suited for Zooey Deschanel and Belle and Sebastian songs, “twee”.