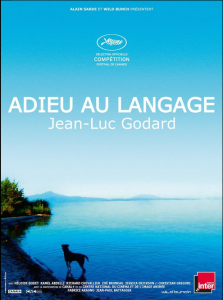

Jean-Luc Godard has been innovating and testing the limits of cinema for over 50 years. This is the man who effectively invented the jump cut decades ahead of its time. His vision and his legacy are unspeakable. With his latest film “Goodbye to Language 3-D” he has found himself ahead of history yet again and this time possibly on the wrong side of it.

Jean-Luc Godard has been innovating and testing the limits of cinema for over 50 years. This is the man who effectively invented the jump cut decades ahead of its time. His vision and his legacy are unspeakable. With his latest film “Goodbye to Language 3-D” he has found himself ahead of history yet again and this time possibly on the wrong side of it.

Using new 3-D to shatter rules of composition and clarity and break down his audience’s comprehension of cinema, “Goodbye to Language” becomes an excruciatingly nonsensical experiment. A narrative is nonexistent. Concrete themes and philosophies are beside the point. Watching it is physically painful, as Godard stages a visual and aural assault on your senses with his cinematography and sound mixing. There is a dog, poop and naked people.

The title “Goodbye to Language” is certainly apt, as Godard has done away with the traditional tools and building blocks we use to communicate. These expectations and rules are constructs that muddle our interpretation of the world; they demand to be broken. But he’s also discarded emotions that would allow us to feel anything while watching his latest avant-garde opus.

Less a movie and more a visual essay, “Goodbye to Language” combines the lives of two couples, one introduced through the subtitle “Nature”, the other through “Metaphor”. The two mirror each other closely to the point of repetition, and the barrage of images toy with our mood at every moment. Students discuss Hitler and literature while operating their smartphones backwards. Over saturated bursts of color adorn babbling brooks and children wandering a prairie. Flashes of Old Hollywood relics interrupt the contemporary. Later, a couple will wander their home in the nude. While the man of the house defecates, he explains that pooping is the only true form of human equality. The woman is not amused, and she’s seen holding a plate of fruit in what A.O. Scott calls “a moment of naturalistic surrealism” in which two major genres of painting have been combined.

Thus judging all this as a movie as we know it betrays the spirit of the work, and Scott again quotes Susan Sontag in arguing “Against Interpretation” and the need to derive a cogent meaning from something constructed out of broken tools.

And yet the film’s most telling shot, one that has been championed as the shot of the year, also highlights “Goodbye to Language’s” failing as visual art on par with Godard’s more charming or emotionally fraught forays into art film over the course of his career.

Godard’s Director of Photography Fabrice Aragno found a way to separate the two images that make up a 3-D image and then rejoin them later in the take. In context of the film, a woman is talking with an older man, but she is then violently pulled away from the conversation and affronted with a gun. The image however rests on both scenes at once, with the overlapping images produced by both the right and left cameras in conflict with one another. The shot is designed such that by closing one eye and opening the other, you can choose which image to view. Taken together, the effect is physically jarring and painful to view, obfuscating anything coherent within the frame. Godard even pulls the same trick again later, this time with a man’s genitals and a woman’s.

In the short time that 3-D has been an available tool for filmmaking and something more than just a gimmick, rules have been put in place designed to simulate how the human eye functions and how to create an illusion of depth. In every use of 3-D during the film, Godard deliberately goes against these norms. Why recreate something you can already see with your eye when you have the technology to imagine something new? There’s texture and depth in the frame but we’re forced to adjust our POV, and nothing on screen is made to look naturalistic to how our eyes would perceive the world.

Using 3-D the way he has, Godard has made a brilliant point, and he’s accomplished something no filmmaker has yet dreamed to attempt technologically. But the way he’s chosen to make this point feels like a direct affront on the viewer. These images are designed to be painful, they’re made to wreck everything we think we know about cinema. With a less high brow, pretentious work of art, we might call that trolling.

Part of me feels like a curmudgeon, casting scorn on something I simply don’t understand and am under prepared for. Many a critic looked like a fool years after they laughed “Breathless” out of the room. They despised Godard’s rapid editing and guerrilla visual style because it went against years of traditional filmmaking that worked just fine. Is it possible that “Goodbye to Language” represents a next wave of filmmaking we can’t yet predict? Will 3-D find a way into a film’s narrative fabric in a way Godard has laid the groundwork for here?

The difference between “Goodbye to Language” and “Breathless” is that with his first film Godard started a New Wave. He and his French peers saw style in certain American films and sought to reinvent their ideas and aesthetic in a way that could accelerate and push film forward. “Goodbye to Language” arrives as part of a technological New Wave, and with Godard’s apparent rejection of the ideas already established, he now seems determined to hold the movies back.

1 star