Sarah Gavron’s “Suffragette” is most relevant today as a piece of historical fiction because issues of women’s rights are in 2015 as prevalent and significant as they were in 1912 London. It’s the slightly fictionalized story of English working women who took up civil disobedience in order to pressure the government to give women the vote.

Sarah Gavron’s “Suffragette” is most relevant today as a piece of historical fiction because issues of women’s rights are in 2015 as prevalent and significant as they were in 1912 London. It’s the slightly fictionalized story of English working women who took up civil disobedience in order to pressure the government to give women the vote.

Should women be allowed to vote? Of course. The answer is so obvious that even the film provides scant arguments against it. “Suffragette” could better advance the discussion of women’s rights in 2015 if it had more to say regarding the debate and nuances of women’s rights issues in 1912. “Suffragette” is more a soapbox than a profound piece of modern feminism. And while it has strong performances and competent filmmaking, it’s even lacking as a stirring piece of dramatic historical fiction.

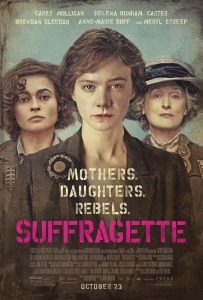

Carey Mulligan is excellent (although what else is new) as Maud Watts, an uneducated mother working in the laundry trade in London. She happens across her colleague Violet Miller (Anne-Marie Duff) smashing West End windows while calling for the vote for women, and she’s reluctantly pulled into the fray. Maud testifies at a parliamentary hearing in place of Violet regarding the pitiful working conditions at the laundry, and the police associate Maud with the other suffragettes (including Helena Bonham Carter and a rapid cameo from Meryl Streep), which is a different term from the non-violent suffragists.

It isn’t long before Maud comes around to the cause, despite how it estranges her from her husband Sonny (Ben Whishaw) and her young son. Sonny is a character who isn’t as monstrous as some of the other male figures in the film, who range from having severe male-gaze/ownership issues to being flat out sexual abusers, but Sonny isn’t quite sympathetic to the cause either. The only meaningful male character with principles of any sort is the police officer played by Brendan Gleeson. He unblinkingly and calmly reasons with Maud that no one cares for her or her activism, and that she’s only being used as a pawn. From Gleeson, the scene hits heavy, and he passively upholds the law without politics in mind and even calls attention to the barbaric treatment of female prisoners later in the film.

“Suffragette” stands out from the crop of most Hollywood movies simply as an example of fiction, historical or otherwise, that allow this many women on screen at once. We see them plotting attacks and even running away from explosions. “Suffragette” even takes on something of a caper vibe, but it lacks a strong sense of suspense to carry along the action. Gavron resorts instead to a lot of shaky cam, naturalistic filmmaking that doesn’t go the distance in terms of creating mood.

During the closing credits, Gavron closes “Suffragette” with a roll of major countries and the year in which they gave women the right to vote, ending with Saudi Arabia promising women the right this year. There is still work to be done, and if nothing else, “Suffragette” is still a rousing story capable of getting more and more women to speak up.

3 stars