Quentin Tarantino, a truly favorite director of mine, can be called a lot of unsavory adjectives, but I never thought “boring” could be one of them.

Quentin Tarantino, a truly favorite director of mine, can be called a lot of unsavory adjectives, but I never thought “boring” could be one of them.

“The Hateful Eight,” his eighth film as he proudly boasts, is an overwritten slog. At three hours and filmed in 70mm Panavision, Tarantino has the audacity to take those cinematic tools reserved for epics and apply them to a cozy, claustrophobic character drama set in a cabin in the woods. Tarantino bottles all his despicable characters and ideas about race and gender into a room and takes forever for them to explode, then even longer to clean up his mess.

The film involves bounty hunter John “Hangman” Ruth’s intentions to collect $10,000 reward by bringing in Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh) alive, a principle of his to personally see all his victims hang. Major Marquis Warren (Samuel L. Jackson) is a former black officer in the Union Army and now full-time bounty hunter who still enjoys killing white boys who would rather see him dead. Warren hitches a ride with Ruth and former marauder, now Sherriff, Chris Mannix (Walton Goggins) to a haberdashery where they’ll wait out a blizzard.

This set up consumes the film’s first of three hours, a drawn out procession of formalities and mistrust in on the nose period dialogue. It’s theatrical play-acting, and Tarantino still confines all their conversation to the two walls of a cramped stagecoach. Tarantino leaves very little to subtext, with Warren, Ruth and Mannix each speaking detailed personal histories despite how much they seem to know about each other already. This is conversation for the audience, a way for Tarantino to show these allies are still at odds with one another, Mannix just a little racist and Ruth very much on edge. The mystery is Domergue, who spends the stagecoach ride with a black eye and a streak of blood down her cheek from Ruth’s blow to the head. She’s a monster, not a lady, we’re told. How much of her abuse can we endure? Tarantino is goading us, and the movie has barely started.

Waiting for them are four other travelers, each an Old West stereotype more likely drawn from cinema than from reality, as is Tarantino’s penchant. Tim Roth plays Oswaldo Mobray, complete with a thick and eloquent British accent that suggests Christoph Waltz could’ve been in mind for the part, as could’ve “Unforgiven’s” English Bob. Demian Bichir as the Mexican keeper of the haberdashery is Bob, easily a surrogate of Eli Wallach in “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.” Bruce Dern is a grizzled and apathetic Confederate General made enraged by Warren’s taunting. And Michael Madsen is the reserved, anonymous cowboy Joe Gage, just off to visit his mother. Of course Tarantino takes the time to have Ruth and Warren reintroduce themselves to all four individually.

No one can be trusted, and Ruth warns that one or some of the remaining four could be in cahoots with Domergue. But to what degree are we invested in seeing whether this woman gets to the rope or not? We have more doubt as to whether they are innocent rather than whether they are guilty. It’s just a matter of how long Tarantino takes to arrive there, and how much we choose to tolerate along the journey. His cards are all on the table.

Or maybe not. Tarantino back tracks in a clunky, narrated aside to fill in the gaps that we didn’t see, rather than allow those twists to emerge through character or dialogue. It’s too contrived to not be exactly as Tarantino intended. We’re made to realize that this genre setting, this overly theatrical dramatizing, this will they/won’t they scenario is in service of how much he can get away with and how hateful he can make his eighth film.

Violence here serves as an exclamation point and punch line rather than a consequence or for stylish entertainment value. The Ennio Morricone score is fascinating, operatic and lovely but staged over extended sequences of Ruth’s driver walking out into the cold to use the bathroom. The N-word rankled some feathers when Tarantino used it as coloring in “Django Unchained,” but here it seems notably superfluous. And there’s not much more to be said for measured storytelling nuance when your characters start projectile vomiting blood onto a woman’s face.

“The Hateful Eight” isn’t just hateful, it’s depressing and a drag. Tarantino has used his time to say everything despicable and nothing in particular.

1 star

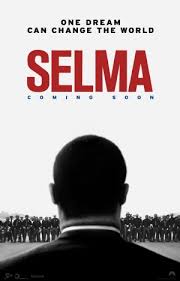

The marches at Selma, Alabama, the boycotting of buses in Montgomery, the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, the protests in New York: these aren’t just part of a “cause”. All this isn’t just “activism”. These are people’s lives at stake, and regardless of which side of the line you stand, blood has been shed both then and now.

The marches at Selma, Alabama, the boycotting of buses in Montgomery, the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, the protests in New York: these aren’t just part of a “cause”. All this isn’t just “activism”. These are people’s lives at stake, and regardless of which side of the line you stand, blood has been shed both then and now.