“The Wind Rises” is Hayao Miyazaki delivering at the top of his game a film pitched differently than any he’s ever made.

There are directors who are acclaimed, and ones who are considered the greatest of all time, and then there’s Hayao Miyazaki.

The man is exalted. Anyone who has seen one of his movies knows him as a household name and knows him not just as a great artist but a “Master” of animation.

News that “The Wind Rises” would be his last film was more news than the film itself. To see a filmmaker retire when his reach has never been greater is near unprecedented, and any film he put out would in its own way be more of a personal statement than anything that came before.

“The Wind Rises” echoes the magical tones of all of his greats, and yet it is pitched at an entirely different tone than the surreal fantasies that invited American kids like myself into a culture of anime and world cinema. It’s both fantastical and bittersweet, coming across as the most grounded movie Miyazaki has ever made.

Telling the life story of famed Japanese aeronautical engineer Jiro Hirokoshi, it first helps to understand it is not a kids’ movie, but that hasn’t stopped Miyazaki from providing the whole experience a colorful, joyous, airy charm. It’s not pure whimsy, but the film opens with a lovely, wordless flight sequence that sets the complex tone.

A young Jiro scurries up a rooftop that undulates and floats, gets into a small aircraft and soars over the town while waving at girls down below. But his dream is rattled when an airship carrying monstrous bombs and baring German insignia materializes in the clouds.

These are the sort of emotions we’re dealing with, the torn rift between creating vehicles that allow flight in wondrous displays of beauty and elation, but are more specifically designed to be machines of war. Hirokoshi was brought up square in the middle of this conflict, and in his creation of the Zero Fighter, Miyazaki tears us between the sleek, manufacturing brilliance of his creation and the knowledge that these very planes killed thousands of both American and Japanese lives in kamikaze attacks.

Miyazaki was likely moved to make this film not because of the simple pleasures of flight or the moral implications his story suggests, but in the parallels Hirokoshi’s tough work decisions reflect on his relationship with his wife. As Miyazaki depicts it, Hirokoshi and his wife Nahoko were madly in love, but she remained deathly ill and required constant care in a sanitarium.

Their conflicting impulses to stay healthy or stay together resonate as strongly as does his choices in his work, giving up speed and lightweight elegance in order to accommodate guns and bombing payload.

“The Wind Rises” is a movie about failure and choices that can be destructive, and yet it encourages us to allow these turbulent sensations to carry us with a quote opening the film, “The Wind is Rising! We must try to live!” It’s a message that fits in snugly with the dark, surreal lessons of adolescence and environmental communion that dominate his other films.

And while “The Wind Rises” is in many ways standard biopic fare, Miyazaki utilizes animation in a way few directors, animators or otherwise, could dream. The 2-D cel shading allows Miyazaki to play with depth perception within the frame, with people appearing larger than life beside background fliers in the skyline. He draws the eyes in conflicting directions, echoing the moods of the film, by superimposing Jiro’s colorful suits and tranquil shots of green pastures alongside weary, gray train passengers or a charred Tokyo devastated by an earthquake. I wouldn’t trade Studio Ghibli’s animation style for the world, but one wonders what possibilities Miyazaki could envision if given the luxury of new 3-D technology.

And one wonders what other stories we might never see from this aging master if this truly is his last film. Ranking “The Wind Rises” among Miyazaki’s best might be a stretch, but this movie shows a man at the top of his maturity and craft as a filmmaker.

4 stars

In just 80 minutes and with absolutely no dialogue at all, the incredibly beautiful animated fable The Red Turtle runs the gamut of the life experience and evokes the presence of God watching over our existence. It’s breathtaking.

In just 80 minutes and with absolutely no dialogue at all, the incredibly beautiful animated fable The Red Turtle runs the gamut of the life experience and evokes the presence of God watching over our existence. It’s breathtaking.

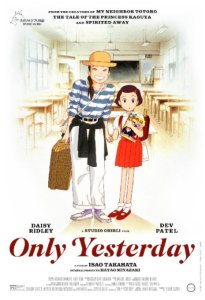

Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.