I found myself this Friday caught in a wormhole of reading articles about gun control. The San Bernardino shooting happened an hour from downtown LA where I now live, and it has stirred up a lot of opinions and emotions.

I found myself this Friday caught in a wormhole of reading articles about gun control. The San Bernardino shooting happened an hour from downtown LA where I now live, and it has stirred up a lot of opinions and emotions.

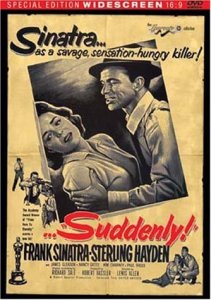

So you can imagine my frustration when the movie I pick for the evening, “Suddenly”, turns out to be a pro-gun movie!

I’ve been pouring through Frank Sinatra’s films for a piece on his centennial, and this one was recommended as a surprising example of Sinatra’s hard-boiled side. Sinatra plays John Baron, a Silver Star winning ex-pat who killed 27 people in the war, but as something of an extension of his PTSD, has now taken a job to assassinate the President of the United States. In the small town of Suddenly, Baron takes a family hostage in order to gain a good vantage point when the President passes through town.

Rumor has it that Lee Harvey Oswald watched the film shortly before killing Kennedy, prompting Sinatra to bury the film for years.

But “Suddenly” has an unfortunate MO that has aged it horribly. The little boy among the family of hostages is Pidge, and he gets the local Sheriff Tod Shaw (Sterling Hayden) to buy him a toy cap gun. His mother Ellen (Nancy Gates) is strongly opposed, but even she’ll come around when the gun factors strongly into foiling Baron, not to mention that even she gets a shot or two off. Director Lewis Allen even gives Baron a cathartic feeling of self-esteem as he waxes on about the beauty and power of gun ownership saying, “When you have the gun, you are a kind of God.”

“Suddenly” often plays like a cheesy ’50s workplace PSA with a story shoehorned in around the war politics. Sinatra’s presence at the beginning of the movie is sorely missed, with the film’s flimsy supporting characters getting developed before we even know what the movie is about, not to mention that all the actors around him are atrocious.

But even Sinatra isn’t much better. Not once, but twice Sinatra plays directly to the camera, wide-eyed and scary in trying to amplify his past demons, but otherwise scowling and grimacing in his typical Sinatra persona and swagger.

“Suddenly” may try to avoid the politics of the time, or the political ramifications of killing the President (Baron at one point mentions the futility of his actions, knowing that as soon as the President is killed a new one will take his place), but with the gun argument front and center, this film is hardly a-political.

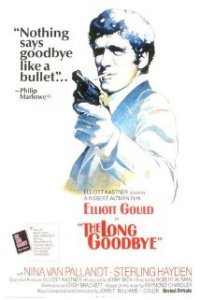

Released a year before “Chinatown”, Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” is the other dense masterpiece of mystery and contemporary noir with a plot so layered it may demand a second viewing to keep it all straight.

Released a year before “Chinatown”, Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” is the other dense masterpiece of mystery and contemporary noir with a plot so layered it may demand a second viewing to keep it all straight.