I was wondering why I had waited so long to see “The Green Mile,” possibly because it has become TNT fodder, possibly because the critical through-line on it has been that it’s “The Shawshank Redemption” with magic, and possibly because it’s on that list of potentially overhyped IMDB Top 250 movies. But none of those reasons really justify how much I loved it.

Now granted, it has its flaws, but whereas “Shawshank” is a much more hopeful movie about survival and perseverance, “The Green Mile” has a wholesome spirituality that wins you over with its inherent goodness. Ultimately, its characters are flawed and even cruel and sadistic, but only one of whom do we really dislike and feel is in the wrong. Director Frank Darabont’s gift is in making a film that embraces its fantasy head-on to make for a wonderfully moving tearjerker.

I myself did not know about the film’s fantasy element, so I will not spoil it here, but it involves the miracles surrounding a massive death row inmate named John Coffey (the late Michael Clarke Duncan) and the prison’s head guard, Paul Edgecomb (Tom Hanks). The movie approaches the giant that is Coffey with the same trepidation that a person would walk the Green Mile before being executed, so it’s a patient film that takes its time over its three hours and allows us to savor every moment. Coffey’s story is one of deep anguish, and in a way, he’s the real emotional center of the film, not Paul.

Paul’s problem involves dealing with one of his prison guard colleagues, the pestilent and cowardly Percy (Doug Hutchison), who is the mayor’s spoiled nephew and feels entitled to be an arrogant little shit. He just wants to see one of these guys cook up close, and he even wants to know what it is to torture someone in one gruesome death sequence. What I like about Percy’s character, if anything, is that as vicious and awful as he is, he reveals himself as ultimately human, pissing his pants out of terror in one scene and revealing that he’s not entirely one-dimensional. We get a sense that he doesn’t entirely deserve the cruel, ironic fate he receives in the end.

Part of me believes that because Paul and his fellow guards are no saints either. They put Percy and their most difficult inmate, Wild Bill Wharton (Sam Rockwell), through both mental and physical brutality. But these characters’ flawed depth allows Hanks to exhibit deep, everyman pain and guilt as only Hanks can. His final conversation with John puts an insurmountable amount of emotional pressure on him that I hadn’t previously imagined.

Some of the scenes, such as the flashback to John’s murder, the execution scene of Eduard Delacroix (Michael Jeter), and the present day tags with Paul as an old man, are a bit heavy-handed and even unnecessarily long, but I’ll remember “The Green Mile” for its more serene moments, not its twists. The use of “Cheek to Cheek” in “Top Hat” is an absolutely beautiful capper. Seeing the mouse Mr. Jingles fetch the thread spool is one of those all time great movie moments. And the rest of the movie is not short of miracles, big or small, either.

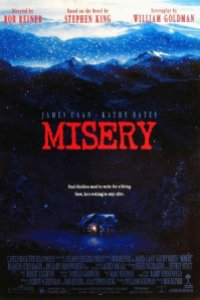

I’d like to see “Misery” remade today with a cute comic book fangirl holding Alan Moore or Stan Lee hostage or something. I think just doing that alone might open up the story to more of a discussion of obsession and fandom than Rob Reiner’s film does, or perhaps for that matter Stephen King’s novel.

I’d like to see “Misery” remade today with a cute comic book fangirl holding Alan Moore or Stan Lee hostage or something. I think just doing that alone might open up the story to more of a discussion of obsession and fandom than Rob Reiner’s film does, or perhaps for that matter Stephen King’s novel.