When Wes Anderson made “Rushmore,” his second film, he desperately tried to get it screened for the film critic Pauline Kael long after she had retired and was close to her death. I’m not sure if her reaction was good, but I imagine the reason he tried to screen it for her was because his film was simply so different. Being released in 1998, it’s not so much ahead of its time because it kicked off this style of film making for the next decade, but it feels very much like a 2000s movie.

How should Anderson have reacted if he had a feeling he was ushering in the next generation of the movies?

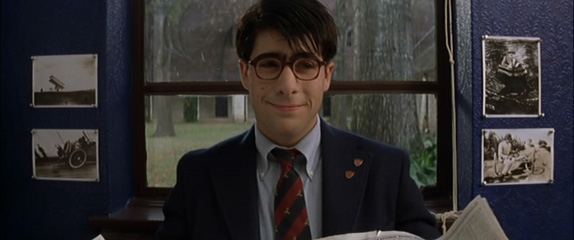

I’ve seen five of six of Anderson’s films, all of them in a peculiar order. “Rushmore” is the movie that put him on the map, along with the film’s co-screenwriter Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman (very young here) and would solidify the sorts of low-key older man roles Bill Murray would take until today.

But my first outing with the director was with “The Life Aquatic of Steve Zissou,” a film that is equally odd and clearly identifiable in Anderson’s colorful yet distant visual style, but features Murray in the lead and seems more “classically” funny. Unlike “Rushmore,” it has what you would call “jokes.”

That’s not to say “Rushmore” isn’t funny; it’s hilarious. It’s to say “Rushmore’s” comedy is very much centered around attitude and absurd attention to detail in a quirky screenplay.

But in fact, all of Anderson’s films play and look in this fashion. That’s what makes him striking as a director. It is impossible to watch even a few moments of one of his movies and not recognize it as such.

The fans he established with “Rushmore” would say he fine-tuned his craft to perfection in “The Royal Tenenbaums,” a film I’ll have to revisit but others have heralded as a cult masterpiece. Then he worked with Noah Baumbach (another disciple of his) on “Life Aquatic” and allowed that quirky attitude to meet situational comedy. And Anderson soon got to the point at which his “The Darjeeling Limited” was overstuffed in Anderson’s style that it felt like nothing more than a vehicle for Anderson’s quirks. Finally is “Fantastic Mr. Fox” what I feel is his finest film. That stop-motion animated picture felt so much like an Anderson movie without sacrificing any of its childlike charm that you wonder why he hadn’t made stop-motion animated films his entire career.

Watching “Rushmore,” it did become obvious that his movies have always felt like cartoons of sorts. “Rushmore” is hardly “about” anything, its characters fit into no reasonable human mold, its scenarios are largely absurd and overblown, yet the characters and the world in which they live are so richly “drawn” that it casts a spell nonetheless.

I’m glad I finally got around to seeing “Rushmore,” as I finally understand Anderson’s significance as a modern auteur of film.