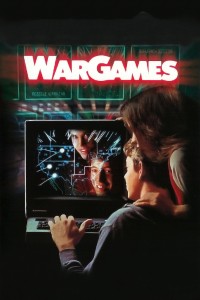

Nostalgia does strange things to people. “WarGames” was a major blockbuster in 1983, the fifth highest grossing movie of the year and even the recipient of three Oscar nominations. I watched it because the film has a prominent place in the book “Ready Player One,” in which the lead character Parzival steps into David Lightman’s shoes and gets to act out the entire movie virtually. And yet it’s strange to think that anyone, even Ernest Cline, would imagine the film has aged well.

Nostalgia does strange things to people. “WarGames” was a major blockbuster in 1983, the fifth highest grossing movie of the year and even the recipient of three Oscar nominations. I watched it because the film has a prominent place in the book “Ready Player One,” in which the lead character Parzival steps into David Lightman’s shoes and gets to act out the entire movie virtually. And yet it’s strange to think that anyone, even Ernest Cline, would imagine the film has aged well.

For one, hacking and even the presence of a NORAD command center for tracking the war were inventive images and concepts that gained some added credibility in pop culture following this film. But it also has to do with the film’s themes, which Roger Ebert argued in his original 4-star review went beyond those of simply being a “Fail-Safe,” Cold War Paranoia knock off. Not only does that not give enough credit to “Fail-Safe,” which feels as tightly wound, crisply made and poignant on a political theory and even a technological level, it’s overselling the virtues of John Badham’s (“Saturday Night Fever“) film.

Broderick in his pre-Ferris Bueller days plays a teenage hacker named David trying to tap into a video game company’s servers, only to stumble across a military super computer programmed to calculate outcomes in a nuclear war with the Russians. Alongside his girlfriend played by Ally Sheedy in her pre-“Breakfast Club” days, David accidentally triggers a war simulation that fools the military generals into believing conflict is imminent.

Computers have no morality, the film attests, only game-like logic. In turn, Badham smartly gives David the same vices. He changes his own grades without any inkling of the consequences, and when he decides to play “Global Thermonuclear War,” he does so recklessly and with gleeful abandon. Like the computer programmed to learn, he’s a kid who needs to mature. It makes for tense, tight and adventurous dialogue, and this added nuance makes the otherwise dryer war room discussions of who pulls the strings, man or machine, more thoughtful. For instance, the film’s General remains the most skeptical, and yet he’s the one most convinced and sucked in by what the computer tells him.

But the technophobia would be a lot more engaging and relevant if even a bit of the scenario seemed plausible. “WarGames” has the appearance of understanding computers, but maybe not humans. Despite no confirmations, no visible proof or no radar evidence, the entire military and President remain convinced that missiles are on their way to destroy everything. In one scene, the government agents assume David must be a spy working with someone on the outside, but it’s a series of dumb misunderstandings. At what point does the film shift from the genuine paradoxes of man vs. machine to just being something of a loony thriller?

I’m also seriously missing Broderick’s Ferris Bueller charms and sense of humor, even if he still has the sheepish quality down. “WarGames” has flashes of a sense of humor, like when David’s father slathers his corn in butter, or when a needle-nosed nerd in a computer lab starts butting in to the tense war drama, but the film lacks the whimsy that someone like Spielberg would’ve given it. And how it ever got nominated for Best Cinematography and was considered to be in the same league as something like “Fanny and Alexander” I’ll never know.

“The only winning move is not to play. How about a nice game of chess?” Those are some of “WarGames” closing lines, and they’re good ones, a whole mess of social theory and Cold War paranoia summed up in one succinct line. Except if that’s the film’s biggest takeaway, it’s hard to say that it really stands apart from the other Cold War thrillers like it.