The ability to compare your girlfriend to an Italian work of landscape art from the Renaissance, to carry out a long distance relationship of casual sex, or to have an affair with your housemate’s girlfriend without consequence, is all decidedly French. Arnaud Desplechin’s “My Golden Days” follows a romance and coming-of-age story very specific to a Parisian lifestyle in the ‘80s, so frivolous and carefree that watching it feels erratic.

The ability to compare your girlfriend to an Italian work of landscape art from the Renaissance, to carry out a long distance relationship of casual sex, or to have an affair with your housemate’s girlfriend without consequence, is all decidedly French. Arnaud Desplechin’s “My Golden Days” follows a romance and coming-of-age story very specific to a Parisian lifestyle in the ‘80s, so frivolous and carefree that watching it feels erratic.

Paul Dedalus (Mathieu Amalric) confesses in casual pillow talk with his current lover overseas that he feels no nostalgia for his country. That romantic tone gets quickly replaced with a flashback to Paul’s childhood, a melodramatic scene of violent domestic abuse. During his pre-teen years, Paul’s mother kills herself and his father checks out altogether.

Back in modern times, Paul becomes detained by a customs official who says a duplicate Paul Dedalus turned up dead several years earlier. In explanation, Paul reflects back on a high school trip to Minsk in the Soviet era when he smuggled in goods and gave his passport to an Israeli refugee. Suddenly the film’s tone assumes that of a tense thriller. Across these different chapters and plays on genre, Paul gets beaten and abused, once by his father, once by his own hand, and once by a jealous boyfriend. And each time Paul describes the situation by saying, “I felt nothing.”

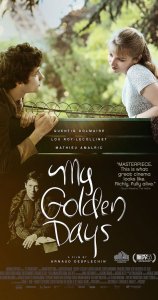

Paul (played by Quentin Dolmaire as a teenager) desperately needs to feel something. The remainder of the film concerns his young-adult relationship with Esther (Lou Roy-Lecollinet), and as Paul’s life becomes consumed with this relationship, Desplechin strives to show how Paul will learn to feel something after all.

Of course, he’ll only learn to feel in a way that matches Desplechin’s (“A Christmas Tale,” “Kings and Queen”) own personal experience in France. “My Golden Days” draws plenty of inspiration from the French New Wave, and even closes with a cheeky freeze frame that feels lifted from “The 400 Blows.” So the revelations and discoveries about life will all be marred in stories of cool young people having sex, arguing with their stuffy, oppressive parents, lying around smoking and dabbling in just a touch of grad-school existentialism. Paul’s character and his experiences are so specific to this culture that it’s hard to truly relate or feel connected to his brand of anguish and grief.

Paul and Esther are both layabouts. He attends grad school but is a lazy student (openly admitting that every class of geniuses needs someone to remind them how brilliant they all are), and she may or may not have settled into a dull, unhappy job after high school, but finds plenty of time to sleep around with Paul’s friends. They’re cavalier about their infidelity and emotionally run hot and cold in the way that teenagers tend to do with first loves.

And “My Golden Days” mimics that frenetic feeling in its style. The early chapters of the movie experiment with tone and framing, with the beginning of Esther’s chapter even briefly employing split-screen wipes that look like something out of an old TV show. Desplechin also uses strange iris close-ups more commonly found in silent film. It’s a way of calling attention to Paul’s more carefree past, and yet nothing on screen feels particularly nostalgic or dreamlike.

It makes for an interesting viewing experience regardless, but like the characters at the center of “My Golden Days,” the film inwardly looks only at itself. Recapping the big moments of his life for Esther, Paul says “I have no idea what else to talk about.” “My Golden Days” isn’t about politics or bigger ideas of the world at large but about these particular people and how they meander through their lives. At the end of the day they might even be interesting, but they still don’t seem to have much to say.

2 1/2 stars