Sometimes the hate or love for a film just doesn’t make sense. In “Kingsman: The Secret Service” and “Jupiter Ascending,” you have two wildly creative films that both look like video games, are trashy fun, feature outlandish performances and stunning special effects, and yet one is considered genuinely good and the other is a cult film, but only because it’s so terrible.

I’ll flip that script and say I believe “Jupiter Ascending” to be a genuinely good movie. Everything about “Jupiter Ascending” is bananas, but the Wachowskis have made an endlessly inventive film that begs pouring over their imagination. Channing Tatum plays a hunter spliced with the DNA of a wolf, and he sports pointed ears, a scruffy blonde goatee and gliding rocket boots, but he fights and acts with the acrobatics of Magic Mike, employing his senses and a holo shield to evaporate pale nymph monsters. Eddie Redmayne gives the definition of a scene-chewing performance, but he seems to know what movie he’s in, curling his fingers in a lilting, vampiric performance. His voice raises octaves as he strives for range, and it never grows tiresome despite how it grows out of proportion. Even the human characters on Earth are colorful, cartoonish Russian greaseballs that make the film ever livelier. And they’re matched by the CGI spectacle of lush palaces and exotic gowns that put “The Hunger Games” to shame. At the same time, we’ll see Tatum flying in front of tacky green screen backdrops made to represent the Chicago skyline, and the film’s artificiality and B-movie charm shine through.

“Kingsman” has just as many quirks and goofy scenarios that extend far beyond the realm of believability, but Matthew Vaughn, as in “Kick-Ass,” has a tendency to confuse pure lunacy and anarchy for style, and gratuitous cartoon violence for humor. “Kingsman” doesn’t actually have sensational stunts. Rather, we see a delirious whooshing of the camera (accomplished digitally) rather than traditional action editing. It allows Vaughn to whip projectiles across the room or zoom in ultra close on various gadgets. One scene has Colin Firth knocking a tooth out of a thug’s mouth, and the tooth hangs in the air in slow motion before flying past another thug’s dumbstruck face. Another is the hyper-violent bloodbath that takes place as a result of Valentine’s mind control. Is there anything about this scene that’s funny other than it’s set to the tune of the “Freebird” guitar solo? And why exactly does Samuel L. Jackson talk with a lisp in this movie?

I still had fun with both of these films, but what’s interesting is how each film approaches class dynamics. It’s rare for movies this trashy to actually have credible substance about society, and yet the fact that they do goes a long way to elevating them beyond their frivolous fun.

Britain of course concerns itself far more with class and upbringing than Americans do generally, so perhaps in Britain this isn’t so revolutionary. But across the pond, “Kingsman” raises some interesting questions. In the film, Eggsy (Taron Egerton) comes from a working class background. When he arrives at the Kingsman training facility, all the other selected candidates are pompous, posh and preppy. They ask whether he’s an Oxford or Cambridge boy, which to anyone in England, coming from “Oxbridge” is an obvious sign of class and snobbery. The film shows that becoming a “gentleman” has little to do with your roots and everything to do with your actions. The film’s set pieces have stakes because they’re as much tests of character as they are feats of strength.

As for Jupiter (Mila Kunis) in “Jupiter Ascending,” the Wachowskis make a point to say that Jupiter was born over the Atlantic, literally without a country and that she’s “technically,” an alien. She explains how astrology has been a guiding factor in her upbringing, and each morning she complains saying, “I hate my life,” as though had she been born under different circumstances, things wouldn’t be so bad. Of course, Jupiter will find that all the wealth and royalty in the world will not make her want to change her heritage and her life.

Both evil plots are also governed by class dynamics. Valentine’s plan is to create a “culling” on Earth, in which the population whittles itself down through mass murder, leaving only the wealthy elite (like Eggsy’s privileged classmate) to survive. The culling process in “Jupiter Ascending” is a bit more sci-fi. The royal families have claims to individual planets, owning them and harvesting their resources like farms in order to extend their lives, but it’s still a process that favors the rich and treats other human beings as second class citizens made to serve.

People have been pointing to the libertarian politics in something like “Captain America: Civil War,” and yet Marvel deliberately makes their films wishy-washy and bland, scrubbed of an explicit position. The Wachowskis and Vaughn may have appeared to make innocent, meat and potatoes action films, but they’re far more sophisticated. Rather, because these are films “of the people” that reject sophistication, let’s just say they have a lot more character.

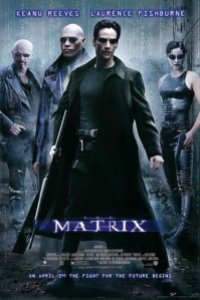

In over 15 years, nothing has aged “The Matrix.” Not two increasingly ridiculous sequels, not a series of box office bombs from the Wachowski siblings, and not the fact that these guys still carry around flip cell phones and interact with the world through pay phones. Movies released just two years later like “Minority Report” look better and more accurate technology-wise than “The Matrix” does, and yet that has not lessened the impact and influence this film still holds.

In over 15 years, nothing has aged “The Matrix.” Not two increasingly ridiculous sequels, not a series of box office bombs from the Wachowski siblings, and not the fact that these guys still carry around flip cell phones and interact with the world through pay phones. Movies released just two years later like “Minority Report” look better and more accurate technology-wise than “The Matrix” does, and yet that has not lessened the impact and influence this film still holds.