One might assume that a film set at the dawn of the new millennium and about the fear of Y2K might feel a hair dated. But while that aspect does, “Strange Days” touches on a subject that’s been more than prevalent in 2015.

One might assume that a film set at the dawn of the new millennium and about the fear of Y2K might feel a hair dated. But while that aspect does, “Strange Days” touches on a subject that’s been more than prevalent in 2015.

Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 film, from a story by Jay Cocks and her then husband James Cameron, imagines through a sci-fi lens what near-future Los Angeles and Hollywood might resemble had race riots never stopped and perpetuated into a mildly dystopian police state. It was released just four years after the Rodney King beating, and it uses the death of an iconic rapper named Jeriko One to act as a martyr and catalyst for all the unrest. Back when the film was released, Tupac Shakur and his eventual death in 1996 came to mind. Today, any of the black men wrongly killed and captured on video will do.

The reason though “Strange Days’s” concept of race feels so poignant has all to do with its sci-fi parameters. In the near future, the police have introduced a tool called a “Squid” that can capture a person’s live experience, from their point of view, as they’re living and experiencing it. People can then enter into “playbacks” that allow you to relive and feel what that person felt.

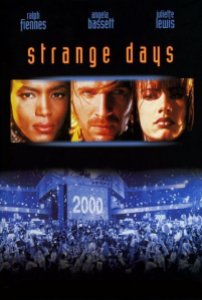

Now the technology is used on the black market, and Ralph Fiennes plays Lenny Nero, the “Santa Claus of the Subconscious” who sells sexual and thrill seeking experiences like it’s a drug. At the start of the film, we witness a crew robbing a restaurant and then falling to his death as he escapes from the cops. Bigelow shoots in a shaky-cam, first person POV that pre-dates found footage films and makes for some gripping action. Lenny himself is an addict for “jacking in”, or “wire tripping”, as Lenny says, as he obsesses over old memories of him with his former girlfriend Faith (Juliette Lewis). But when someone starts leaving threatening videos for him to watch, Lenny and his tough friend Mace (Angela Bassett) are on the run from both a madman and a pair of renegade cops.

The plot twist for what’s causing Lenny to be on the run is captured in a video involving the death of Jeriko, and it inherently brings to mind the cell phone videos that have sparked protests today. But after the events of the past year, one has to wonder if the outrage, animosity and eventual justice seen here is just another part of “Strange Days’s” fantasy.

Part of the problem with “Strange Days” is that the race riots are hardly even the main focus of the film. Made for $42 million back in the ’90s, the film was a giant flop that raked in only $7 million. One of the film’s trailers touches on just how all over the place “Strange Days” is, with a heavy focus on the sci-fi, a conspiracy mystery and the fear of what’s to come on New Year’s Eve 1999.

That’s not to say Cameron and Cocks’s story is bad or unfocused, but it drags to over two and half hours and feels like it has two endings, one to confront the sadistic madman threatening Lenny and Faith, and the other to confront the cops who want the tape Lenny is hiding. And the thread connecting these two plot strands is tenuous at best.

But you wish Bigelow did take a bigger interest in the unique sci-fi angle of the story. “Strange Days” becomes strictly procedural in its last hour or so, whereas other sci-fis that take us inside people’s minds, like “Minority Report,” “A.I.,” “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and “Being John Malkovich”, to name just a few, go deep into psychological implications; “Strange Days” only considers these brain-teasing pleasures and consequences superficially.

Bigelow does however put the POV perspective to powerful, action heavy use, implicating the viewer in some of the film’s more depraved moments. If you thought Bigelow was advocating for torture in “Zero Dark Thirty” and that those scenes were rough, try on the rape scene in “Strange Days”. A masked intruder sneaks into a woman’s hotel room and begins to rape and strangle her, but before he finishes, he places a viewing device on her head, forcing her to watch herself die from the eyes of her killer. Lovely.

That scene could be debated for days. More simply however, while Angela Bassett kicks ass and dominates the screen in Bigelow’s stylish fights, and Juliette Lewis commands a a handful of grungy rock performances, Ralph Fiennes seems strangely miscast. Only his fifth film role at the time, it’s hard to imagine him as the steamy count in “The English Patient” or the sinister Amon Goethe in “Schindler’s List”, let alone any of his more recent iconic roles. He has the sleazy, slick, fast-talking demeanor of James Woods and the ’90s haircut of Nicolas Cage. He’s not the action star, but audiences should appreciate the depth he and the cast bring to “Strange Days’s” more melodramatic moments.

If anything, the interesting foibles of “Strange Days” demonstrate that Bigelow was well on her way to becoming a master. It’s just hard to “jack in” to that frame of mind.