Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

Out in the Japanese countryside, budding yellow flowers dot the fields, trees line the horizon and a stream cuts through the valley. From the top of a hill, you learn that over hundreds of years, everything you can see has been man-made. In “Only Yesterday,” Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli animated film from 1991, the farmer Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba) explains to the visiting Taeko (Miki Amai) that on this farm, “Every bit has its history.” Each moment of Takahata’s film shows that a person’s experiences shape their life and identity. There’s history and beauty in even the most mundane and ordinary moments of life.

For her vacation from work in the city, 27-year-old Taeko decides to visit her family in the countryside to work on their farm. As she travels, she reflects back on her life as a child. The 10-year-old Taeko (Youko Honna) is spunky, sunny and just a little bashful and spoiled. She’s a typical little girl, so overwhelmed with joy as she visits a bath house that she faints, mystified by how to cut open a pineapple, and so smitten and petrified in her crush on the cute, 5th Grade pitcher of the baseball team.

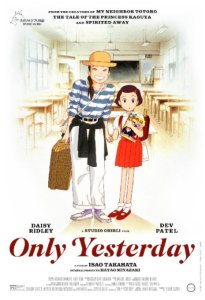

“Only Yesterday” shares the look of all Studio Ghibli animated films, with soft pastel colors and rich, painterly, hand drawn detail within every frame. But unlike the fantastical tropes of Hayao Miyazaki’s many films within the studio, Takahata grounds “Only Yesterday” in reality. The film’s modest scale only make the many slices of life more beautiful.

Takahata made the film back in 1991 (since then he’s been nominated for an Oscar with “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya” in 2013), but Disney originally blocked its American release due to a scene in which the naïve kids start piecing together what it means to have a period. Sure enough, “Only Yesterday” approaches many mature, adult themes through young eyes. Similarly, Takahata’s masterpiece “Grave of the Fireflies,” his previous film in 1988, deals with war, violence and death in a way that perhaps a child can understand.

“Only Yesterday” however finds tragedy in smaller moments. In one scene, Taeko gets a single line in a play, and though she’s discouraged from improvising new lines, she makes the most of it in her performance and gets offered a part in a college production. Her fantasy about fame blooms to life in preciously hilarious pinks, yellows and greens around her. It’s adorable, and it’s so intimate that it hurts all the more when her father quietly puts his foot down and dashes her dreams. In another, Taeko gets a D on a math test because she doesn’t understand dividing fractions. She draws a picture of an apple and cuts it into pieces, so she’s clearly practical, but her older sister thinks there must be something wrong with her, and it’s devastating to see Taeko within earshot of her sister’s ridiculing.

Of course the spirit of any Studio Ghibli movie lies in its animation. Every film that has ever come from this studio has a meticulous, loving care in each still frame. Takahata literally blurs the frame itself to give “Only Yesterday” a hint of magic. After a baseball game, Taeko quickly runs home to avoid the boy she has a crush on. Though he’s just as bashful, the boy chases after her, and there he is, standing in the distance, a small figure at the end of an alley. The bright orange sunset is just behind him, and everything else in the frame is white and washed of its color, with the edges of the foreground specifically erased to create a sense of depth within the 2D, animated frame. He mumbles out a question: “Do you like sunny, rainy, or cloudy days?” She stutters out her answer, “c-c-cloudy,” they both smile, and he runs off. Taeko then turns down the block and starts to seemingly climb up the frame and fly away. You’ll melt watching it.

“Only Yesterday” drips with warm, fuzzy sensations of nostalgia. The childhood story and characters are whimsical and light-hearted but are concerned with intimate, personal truths about life in a way that would be meaningful at any age.

4 stars