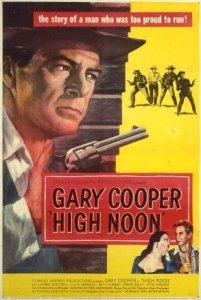

Gary Cooper’s Will Kane wears a black cowboy hat throughout “High Noon”. The fashion choice is by design. He’s a hero, but by the end his victory is hollow. The town’s people he has sworn to protect have all left him for dead, for various reasons, and when he’s finally fulfilled his duty, he retires out of disgust, not achievement. In the film’s final moments Cooper wordlessly casts his “tin star” to the ground and rides off on a cart with his newlywed wife Amy (Grace Kelly in her first role). For a movie about a man who nobly puts loyalty to his job ahead of loyalty to his family, it’s more bitter and callous than inspirational.

Gary Cooper’s Will Kane wears a black cowboy hat throughout “High Noon”. The fashion choice is by design. He’s a hero, but by the end his victory is hollow. The town’s people he has sworn to protect have all left him for dead, for various reasons, and when he’s finally fulfilled his duty, he retires out of disgust, not achievement. In the film’s final moments Cooper wordlessly casts his “tin star” to the ground and rides off on a cart with his newlywed wife Amy (Grace Kelly in her first role). For a movie about a man who nobly puts loyalty to his job ahead of loyalty to his family, it’s more bitter and callous than inspirational.

That end is enough to earn “High Noon” the title of an anti-Western, and with it a reputation as one of the best American Westerns ever made (it currently sits at #221 on the IMDB Top 250). Its hero Will Kane is full of fear and uncertainty, and he’s without confidence, support or even a strong sense of logic or values toward why he’s risking his life for this town. The cynical end following the climatic shootout is further one that calls out the McCarthy era fear-mongering and politics circa 1952, when the film was nominated for seven Academy Awards and took home four, including one for Cooper for Best Actor. Fred Zinnemann’s (“From Here to Eternity”) film in a script by Carl Foreman (“The Bridge on the River Kwai”) casts scorn on the townspeople who are all too cowardly, greedy, spiteful or all three to help Kane kill the vengeance driven Frank Miller and his posse, who aim to gun down Kane once Miller arrives pardoned from prison on the noon train.

But so many of the best Westerns are already anti-Westerns. “The Searchers” grapples with vicious racism and hatred toward Native Americans in John Wayne’s hero. “Johnny Guitar” is a wild, feminist, damn near exploitation film. Later entries in the genre like “Unforgiven” remove some of the romanticism of the old West by focusing on an aging gunslinger. “High Noon” may have been one of the earliest anti-Westerns of its kind, but its innovations stop there.

Working in its favor is the real-time element, with characters constantly checking the clock and building up the myth of the demon set to arrive on that High Noon train, Frank Miller. It leads to a wonderfully effective use of sound, in which Zinnemann cycles through the town people in stark close-ups, only to be abruptly cut off by the sound of the train arriving at the strike of noon.

Equally effective is how every character in the small town of Hadleyville, no matter how cowardly, weaselly or vindictive they are, their personality is tied to the arrival of Miller on that train. One of Foreman’s more powerful twists is in revealing to us that Kane’s presence, despite his ability to clean up the town and run Miller out, has not been entirely welcome. Business at the hotel has dried up, more people had work as deputies, and many even called Miller their friend. It’s not just that Kane is a man without a country, but that even those who care most for him feel its in their best interest to see him leave town or fail.

“High Noon” however has aged horribly. It’s a prime example of an effective, Old Hollywood screenplay in which the dialogue is earnest, but thick and bluntly ineloquent. The characters have clearly drawn motivations and back stories, but everything is telegraphed. So much of the film is without action or personality coloring that the constant, Stanley Kramer led ideology can get weary. Whether its the simplistic views of what it will take Lloyd Bridges’s character Harvey Pell to become a man, or the recurring “High Noon” theme preaching “don’t forsake me oh my darling” whenever Kane ambles through town, Zinnemann’s hammy execution just doesn’t hold up as well as the edgy bent of Westerns by John Ford or Howard Hawks.

That changes slightly in the film’s famous shootout, in which Kane is resourceful and human more than just a slick quick draw. Zinnemann strips virtually all the dialogue in this sequence and even finds quick catharsis for Kane and his wife Amy.

“High Noon” has a lot going for it, and it’s likely a good entry point into Westerns, but a real classic it is not.