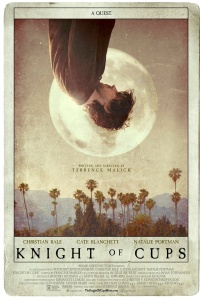

In ways that are both enlightening and maddening, Terrence Malick continues to demonstrate in his latest film “Knight of Cups” a remarkable eye for visuals and creative ways of playing with depth. Since “The Tree of Life,” Malick’s polarizing masterpiece, critics have divided on whether Malick’s movies have grown tired, in that they’re beautiful and breathtaking, but too much like all his others.“Knight of Cups” follows in “Tree of Life’s” tradition as a dreamy, formless, spiritual, often indulgent film of a man drifting through life as hushed voiceovers adorn the images. But in small ways, Malick shows he’s still experimenting and innovating within his style, employing the now three-time Oscar winner Emmanuel Lubezki to engineer turbulent, liberated and delirious fish-eye shots using GoPro cameras. At times the film arguably looks more like Jean-Luc Godard’s “Goodbye to Language 3D” than it does “The Tree of Life,” and you wonder what brilliant and creative things Malick might do in 3D or another new format. And lord knows that with Lubezki he has the means.

In ways that are both enlightening and maddening, Terrence Malick continues to demonstrate in his latest film “Knight of Cups” a remarkable eye for visuals and creative ways of playing with depth. Since “The Tree of Life,” Malick’s polarizing masterpiece, critics have divided on whether Malick’s movies have grown tired, in that they’re beautiful and breathtaking, but too much like all his others.“Knight of Cups” follows in “Tree of Life’s” tradition as a dreamy, formless, spiritual, often indulgent film of a man drifting through life as hushed voiceovers adorn the images. But in small ways, Malick shows he’s still experimenting and innovating within his style, employing the now three-time Oscar winner Emmanuel Lubezki to engineer turbulent, liberated and delirious fish-eye shots using GoPro cameras. At times the film arguably looks more like Jean-Luc Godard’s “Goodbye to Language 3D” than it does “The Tree of Life,” and you wonder what brilliant and creative things Malick might do in 3D or another new format. And lord knows that with Lubezki he has the means.

Yes, “Knight of Cups” is still very “Malick-esque,” but for all its excesses, “Knight of Cups” still feels beguiling as a thoughtful, artistic look at existentialism, at examining what it means to be alive, even amid so much excitement, sex, opulence and hedonism.

“You think that when you reach a certain age things will start to make sense. That’s damnation. They never come together. Just splashed out there.” Malick explores this thesis throughout “Knight of Cups” both thematically and formally. Watching it is like witnessing a flashback of a life as an otherworldly spirit. The film’s weightless camera wanders around to observe moments and emotions rather than a concrete story. Everything’s “just splashed out there,” disconnected in ways that can be as frustrating as they are invigorating.

Our vessel is the wealthy Hollywood playboy and screenwriter Rick (Christian Bale). He revisits the relationships in his life, from fast friends, past lovers, bosses, brothers and fathers, and in each encounter he drifts without much feeling or words to articulate his mood. One of his girlfriends, the punk, free spirit Della (Imogen Poots), challenges his depression with the question, “Am I bringing you back to life?” With his reckless brother Barry (Wes Bentley), he can communicate entirely through posturing and body language. His ex-wife Nancy (Cate Blanchett) still loves and hates Rick passionately, but likely knows more about him than he ever will.

The title “Knight of Cups” refers to a tarot card and fairy tale of a man who can’t remember he’s the king’s son after drinking from a special cup. Each of Malick’s vignettes, as broken up through chapters, shows a man trying to remember who he is and who he was. Other films have shown men disillusioned with their life of wealth, women and splendor. But in “Knight of Cups,” even during a massive, celebrity-cameo filled party sequence at a glorious palatial estate, the film’s graceful editing, score and cinematography suggest something beyond just Rick’s glittering anguish.

Even a trip to Las Vegas finds a new mystique through Malick’s eye. It’s lush and beautiful rather than loud, sensational and trashy. He’s separated the confetti-filled, neon colored raves from their typical emotions and associated them instead with something gorgeous and ethereal. In Malick’s Vegas, there are as many peaceful, Zen moments as when he takes Rick inside a tranquil Buddhist monastery.

At a certain point however, the film’s weightless quality itself does grow aimless, even anemic. If “Knight of Cups” observes a life in progress from afar, then sure enough it will be filled with highs, lows and even boredom. How many impeccable shots of beautiful women frolicking barefoot on the beach can you honestly have?

There’s no doubt that Malick’s latest has some indulgence and seriously inscrutable moments. It falls short of “The Tree of Life’s” masterful reverie but surpasses the drearier slog of his last film, the equally formless “To the Wonder.” But “Knight of Cups” is its own film, and rather than turning in on his own bad habits, Malick is just beginning to find new meaning in the world.

3 ½ stars