How do you have a Hunger Games movie without the Hunger Games? That was essentially the problem of “Mockingjay – Part 1,” the padded first half to the third and final entry in Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games book trilogy. “Part 2” finds a way to retain that Hunger Games feel without the repeat of the arena setting, and it finds Francis Lawrence’s film back on track for a satisfying conclusion to what has been an otherwise stellar franchise.

How do you have a Hunger Games movie without the Hunger Games? That was essentially the problem of “Mockingjay – Part 1,” the padded first half to the third and final entry in Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games book trilogy. “Part 2” finds a way to retain that Hunger Games feel without the repeat of the arena setting, and it finds Francis Lawrence’s film back on track for a satisfying conclusion to what has been an otherwise stellar franchise.

The rebel organization housed at District 13 has rescued Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) from the Capitol’s imprisonment and brainwashing, but at the end of “Part 1” he tried to murder Katniss (Jennifer Lawrence) and is still suffering from the after effects of the brainwashing. Katniss hopes to bring him back to the real world while organizing a plan of attack to bring down President Snow (an increasingly excellent, understated and chilly Donald Sutherland). The rebel leader President Coin (Julianne Moore) wants to use Katniss as a symbol for the rebellion, but Coin may be plotting a way to kill Katniss and get her out of the way in the event of Coin’s inevitable takeover and rise to power.

All this has traces of the politicking that bogged down “Part 1,” but “Part 2” is far better at reaching those intimate, character driven pow-wows and moments of conflict. Watching and waiting for the film to get to the action, Director Lawrence keeps the audience of two minds, torn between a craving for excitement and Katniss’s want for peace. For the first time in the franchise “Mockingjay” makes the dividing line between good and evil less clear. Katniss comes to realize the people trying to kill her are not her enemy, every drop of blood lost has less and less meaning, and the impact of each on the audience stings more.

“Part 2” gives back the “Hunger Games” feel by trotting Katniss, Peeta, Gale (Liam Hemsworth) and her outfit of teenage Marines into the barren warzone of the Capitol. The streets are littered with “pods” or cleverly designed booby traps. Their unmanned nature makes each feel gamelike, with someone from above pulling the strings and all the rules being decided on the fly. “Mockingjay” toys with everything from stormtroopers, flamethrowers, machine gun traps, spotlights capable of disintegrating and even slimy, faceless zombies that resemble the pale monster in “Pan’s Labyrinth.” One incredible set piece has the team running from a growing pool of oil; touch the surface and you’re immediately impaled by spears of the liquid suspended above the ground.

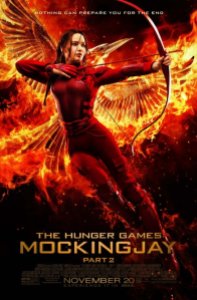

“The Hunger Games” have always stood out in the creative use of deadly traps and special effects, but it’s also one of the few that goes so far above and beyond the YA novel boilerplate romance and “be yourself” mantra. The symbolism here is all on point, with Katniss literally becoming the “girl on fire” after an explosion, with the floating packages previously used in the games as relief now used as harbingers of death, and with the televised murders of children not just used for action but to implicate us as an audience for enjoying it.

The very first “Hunger Games” showed this was not a trifling franchise just for kids. Katniss is a character in grief and anguish, the world is always in disarray, and love triumphs, but at a cost. “Mockingjay” ends this franchise fittingly; the odds were ever in its favor.

3 ½ stars