Watching “Planet of the Apes” today is like trying to sway a climate change denier or a Creationist: it’s not going anywhere and after a while it gets pretty tiring.

Watching “Planet of the Apes” today is like trying to sway a climate change denier or a Creationist: it’s not going anywhere and after a while it gets pretty tiring.

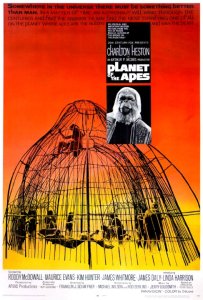

Franklin J. Schaffner’s film came out in a period of civil and racial unrest in 1968. Martin Luther King Jr. was even shot and killed the next day after receiving its wide release. It speaks directly to racial fears and the hatefulness that leads to ignorance and abuse. By flipping the script of racial politics into one of man vs. ape, it packs big ideas into a flashy, fun genre film of the Old Hollywood tradition. Except just before its famous ending it almost asserts the superiority of man, with Charlton Heston standing as its virile leader. The cynical ending in front of the Statue of Liberty proves that man is ultimately no better than beasts, responsible for their own demise through their vices of lust and greed that the ape culture has rejected. But there’s a degree to which the damage has already been done, suggesting that the future of a different breed being superior to the white males is a scary one.

“Planet of the Apes” perhaps isn’t as explicit about race or animal rights as it could be, opting more broadly to be about human nature. But whereas the newer sequels “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” and “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes” have tied the series more to environmental concerns than racial ones, sitting through the original can be awfully frustrating when dealing with characters so obviously stubborn and hateful.

The scene that comes to mind places Heston’s astronaut George Taylor at the center of a trail. He and his friendly ape protectors Cornelius and Zira are accused of heresy against ape law and religion. The judges, including the protector of the faith Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans), immediately write off and overlook anything Taylor does as a hoax. He can talk, he can understand ape language (conveniently, English, even over 2000 years in the future), he can write, but you know no matter what he does they’re not going to budge, so why bother? The film’s more interesting moments happen before the men come across any apes, with Heston smugly challenging his travel companion’s existential views on trying to achieve fame and immortality. Now over 2000 years old, Heston says, “You got what you wanted. How does it taste,” before cackling maniacally as he plants an American flag, a symbol that has long lost its meaning.

Surely such discussion was highly thought provoking back in 1968. Or maybe not. Cliche idioms like “Man see, man do,” or “to apes, all men look alike,” were as cheesy then as now, if not more so. But today the subject has grown tired and has evolved beyond such obvious racial distinctions. I can still turn on cable news today and find people just as resistant to change, but “Planet of the Apes’s” antiquated views beg for something more sophisticated in today’s political climate.

Of course, “Planet of the Apes” has aged really poorly when you consider it came out the same year as “2001: A Space Odyssey.” It would be really hard to argue that the makeup effects still look “good,” but they’re certainly not distracting. More distracting is Heston; he has remarkable charisma and screen presence but was one of the hammiest actors of his generation. Here he’s embracing his more primal nature in his performance, practically beating his chest and howling as he’s being sprayed by a hose or chasing through the streets. But even when his character is supposed to be sincere, holding up a man’s old glasses, false teeth and heart valve, Heston still feels cocky and diminutive to the weakness of humans other than him.