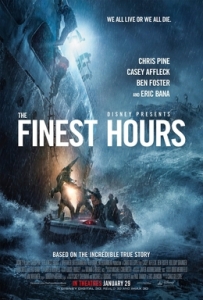

The members of the Coast Guard don’t get the credit that cops, firefighters or soldiers do for saving lives. “The Finest Hours,” Disney’s telling of an historic rescue mission, is full of heroics but also people just doing their job. It’s a sentimental, old-fashioned thriller but is also endearingly modest.

The members of the Coast Guard don’t get the credit that cops, firefighters or soldiers do for saving lives. “The Finest Hours,” Disney’s telling of an historic rescue mission, is full of heroics but also people just doing their job. It’s a sentimental, old-fashioned thriller but is also endearingly modest.

Chris Pine is known for playing the hot-shot, loose cannon Captain Kirk in the “Star Trek” movies, but here he’s Bernie Webber, stationed on the coast of Cape Cod in the winter of 1952. Webber is timid, sheepish, apologetic and looking to please. In front of his bride-to-be Miriam (Holliday Grainger) he practically melts. Miriam is everything he’s not: confident, forward and even willing to ask him to get married.

Webber isn’t the only timid one. A few miles out to sea Ray Sybert (Casey Affleck) is aboard a sinking tanker caught in a violent storm. In a remarkable shot, a seaman stops short on a broken bridge to discover that the entire ship has split apart with the front half suddenly barreling toward him before plunging into the ocean. Sybert knows the boat up and down, but no one quite likes his introverted demeanor or appreciates him tucked away in the engine room. When we see him nervously explaining their situation to a reluctant crew looking to abandon ship, Affleck plays Sybert hunched between bodies, quietly and calmly stating his plan as he peels open a hard boiled egg. Both Pine and Affleck are uncharacteristically understated and are the heart of the movie’s sentimental charms.

The twist involves a second tanker that has also split in two and has dividing the Cape Cod crew, leaving Webber, his inexperienced team and a tiny, 36-foot motorboat the only chance for Sybert and the remaining sailors biding their time.

Will the Coast Guard save the day? Take a wild guess. “The Finest Hours” remains bloodless and predictable, even contrived as Miriam forces her way into the office of Webber’s commanding officer (Eric Bana) or when one of the trapped sailors (John Magaro) pettily challenges Sybert’s manhood. But the film is not without danger or suspense. The waves keep getting bigger, the sea grows darker, and the stakes more impossible as time runs out.

Director Craig Gillespie (“Million Dollar Arm,” “Lars and the Real Girl”) has the finest special effects available to him, whether in its impressive set design, some stunts that take the Coast Guard’s small boat inside the curl of a wave, or in its flashy digital, 3D cinematography that swoops from the ship’s deck to its hull in a single unbroken take. And everything has a wintery color palette that makes the film look decidedly classical.

It’s no surprise Disney made a movie in which the heroes are transformed into underdogs who have to overcome their insecurities and fears. More surprisingly, “The Finest Hours” feels muted in its storytelling and its heroics. These characters are the humble second-string guys just doing their job rather than the first responders. And the film remains epic despite being a rescue mission for just 30 people instead of 30 million.

For telling a good story well, give the Coast Guard and “The Finest Hours” some much deserved and long overdue credit.

3 stars

There’s a moment in “Out of the Furnace” when a backwoods, villainous hick named Harlan DeGroat has a deer skinned to its bones hanging from the ceiling. The imagery calls to mind something absolutely raw, as though this bleak look at Americana symbolized all that’s emotional and open about the people who live this way. But Director Scott Cooper’s prized trophy doesn’t have that much meat on its bones to begin with. “Out of the Furnace” feels frustratingly unspecific, empty and generic, no matter how gritty the characters are.

There’s a moment in “Out of the Furnace” when a backwoods, villainous hick named Harlan DeGroat has a deer skinned to its bones hanging from the ceiling. The imagery calls to mind something absolutely raw, as though this bleak look at Americana symbolized all that’s emotional and open about the people who live this way. But Director Scott Cooper’s prized trophy doesn’t have that much meat on its bones to begin with. “Out of the Furnace” feels frustratingly unspecific, empty and generic, no matter how gritty the characters are.