Our first look at the kids of “Beasts of No Nation” is through the hull of a broken old box TV. With no screen inside, the camera peers at a distance through the empty frame at these African children playing soccer. We’ve seen these children from the safety of our computers and know little else (ironically, “Beasts” is Netflix’s first original feature and will be consumed almost entirely on smaller screens). We don’t always know exactly where they’re from, and “Beasts” in turn is set in an unspecified West African nation. What are invisible to us are the directions and futures of these kids. Director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s film illuminates through war torn violence and brutality just how without a nation these young people are.

Our first look at the kids of “Beasts of No Nation” is through the hull of a broken old box TV. With no screen inside, the camera peers at a distance through the empty frame at these African children playing soccer. We’ve seen these children from the safety of our computers and know little else (ironically, “Beasts” is Netflix’s first original feature and will be consumed almost entirely on smaller screens). We don’t always know exactly where they’re from, and “Beasts” in turn is set in an unspecified West African nation. What are invisible to us are the directions and futures of these kids. Director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s film illuminates through war torn violence and brutality just how without a nation these young people are.

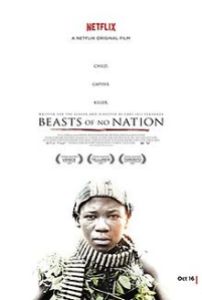

The film tells the story of Agu (Abraham Atta), a young boy living in a poor refugee village in West Africa. When the military arrives, his mother escapes but is forced to leave her son behind in a rough, immediate coming of age. “You’re with the men now,” his father and brother say. When the soldiers kill his family, Agu escapes into the forest and comes upon the Commandant (Idris Elba) and his army of rebel warlords.

Agu becomes a reluctant member of the band of warlords, but finds direction and guidance in the Commandant’s leadership and fatherly wisdom. He speaks of young boys’ ability to be just as dangerous as the men, and he swiftly slits the throats of any who fail an initiation beating ritual. Through something of a spiritual transformation as Fukunaga stages it, Agu becomes part of a travelling family. They leave no trace or shelter as they march toward the country’s capitol.

To further deepen Agu’s isolationism, “Beasts” abandons the use of an African native language in favor of English once Agu joins the Commandant’s ranks. Like the famous long tracking shot during Fukunaga’s first season of “True Detective”, several set pieces here chase Agu’s abuse and blind, war torn rage. In one scene, Fukunaga makes us endure Agu being forced by the Commandant to take a machete to a prisoner’s skull. It’s a moment without much nuance, only brutality and Agu’s loss of innocence.

Fukunaga is an expert at capturing the bleak naturalism of whatever setting he’s in, be it the Central American slums in his first feature “Sin Nombre,” the Victorian period of his “Jane Eyre” adaptation or deep in rural Texas in “True Detective.” His work here (Fukunaga served as his own DP) captures a beautifully horrific shot of helicopter hellfire from the perspective of the foot soldiers on the ground. We see golden, fiery rain and shooting stars peppering the sky, a relief amid many of the film’s earthy tones.

But as in “True Detective”, Fukunaga is at his best walking the line of the naturalistic and the surreal. Fukunaga takes Agu through blood red soaked trenches, with the camera seemingly crawling to attain domineering low angles even at Agu’s short height. In another, the lush greens of the forest change to a hellish pink, with the world seemingly moving faster in the background.

“Beasts of No Nation” goes above and beyond that of a coming-of-age story in which a child is pushed into depravity. The film takes a left turn when the Commandant is summoned to see his politician leader, an uncharacteristic scene that further complicates the bunch’s goals and pursuit for survival. “Beasts of No Nation” is a film about the strength of the young and their uncertain future, and while Elba is powerful in a role that immediately commands respect, it’s first time actor Attah who shows the most range, notably in “Beasts’s” chilling closing scene.

Fukunaga’s first film “Sin Nombre” was a movie also about poor refugees desperate for survival as they tried to ride the rails out of Central America to life in the States. They faced terrors and senseless violence along the way, but they at least had a clear direction and destination in mind. For Agu and the other kids of “Beasts of No Nation”, they don’t even know what war they’re fighting for.

3 ½ stars