We’ve grown used to the darkness. We’ve come to expect films to not have everything plainly visible and bright on camera, to see shadows and shades of color and light in the way we experience the world naturally. We’ve also come to see our heroes and our stars to make themselves look ugly, to hide in the shadows, to transform themselves, and to help make our viewing experience something other than natural, something disturbing and unusual.

We’ve grown used to the darkness. We’ve come to expect films to not have everything plainly visible and bright on camera, to see shadows and shades of color and light in the way we experience the world naturally. We’ve also come to see our heroes and our stars to make themselves look ugly, to hide in the shadows, to transform themselves, and to help make our viewing experience something other than natural, something disturbing and unusual.

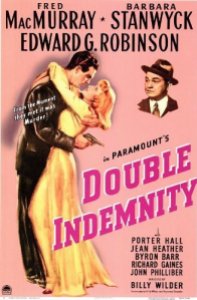

I’m currently taking a course on Neo-Noir films, and our professor Drew Casper showed us clips of “Double Indemnity”, howling at the film’s introductory shots as he did at how dark they were, how many shadows could be seen on screen, how detailed and rich the sets were, and how much it looked like a film of the German Expressionist period. “This is a Hollywood film,” he screamed. “That’s the star! And his back is to the camera!”

Is it that hard to distance ourselves from the time and era in which we’re watching a movie? Can you imagine anyone watching the opening of “Nightcrawler” (the first week’s screening) and being SHOCKED that when we first see Jake Gyllenhaal’s Louis Bloom his back is to the camera, or that his face is partially darkened in the light?

Old Hollywood though really did have a fetish for making things look gorgeous. Everything was well lit and made to look stunning, even if that meant light came from unnatural places, or even if the scene was dramatic and grim. It took a foreigner like Wilder to break everyone out of the habit. Wilder was hardly the only or the first, and “Double Indemnity” is only a seminal work because it’s one of the finest, earliest examples of the form in American cinema. It holds up wonderfully today, even if its innovations don’t leap out and grab you in the way they once did.

Roger Ebert wrote very plainly in his Great Movies review of “Double Indemnity” that “the enigma that keeps it new, is what these two people really think of one another. They strut through the routine of a noir murder plot, with the tough talk and the cold sex play. But they never seem to really like each other all that much, and they don’t seem that crazy about the money, either. What are they after?”

The truth is “Double Indemnity” is a movie about greed, not about love and especially not about the perfect murder or the thrill of the pursuit. And Walter Neff and Phyllis Dietrichson (Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck each at their absolute best) find that greed through sex, wordplay and their own desire for one another, if for no reason other than they’re present. Some of my favorite dialogue turns up as soon as Neff enters the Dietrichson home and catches Phyllis after sunbathing. “It’s two F’s, like in Philadelphia… You know the story. ‘The Philadelphia Story'”.

They’re hopeless and obvious flirts, with Neff in particular going cocky and rogue without hesitation. What’s more, he’s the one who rigs their scheme to the point that it gets them caught. He demands they play it straight, but then he goes for broke by arranging for “Double Indemnity”, not just to dump the body but get double the payment by doing it on a train.

Part of what makes “Double Indemnity” such an effective noir is that the tension is not in the murder itself. We have a lot of movie left once Mr. Dietrichson is dumped on the train tracks. The dogged suspicion of the claims manager Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) is intense. He blows the movie wide open with a series of reversals that seal the couple’s fate. They don’t crumble under guilt or slip up out of a love for one another. Their greed just gets paid back big time…and double.