In his breakout film “MASH”, Robert Altman set his war comedy in the midst of the ‘50s and the Korean War, but every line of dialogue and moment of anarchy was pure ’70s. The characters are obsessed with sex and the swinging, free love attitude that carried over from the ‘60s. They’re anti-establishment in a way that’s more “Cool Hand Luke”-cheeky than “Rebel Without a Cause”-angst-y. And the visuals on display are often somber and bloody in the New Hollywood fashion rather than melodramatic.

Robert Altman was the ‘70s. Across multiple genres and points in history, Altman always made movies for his time. Directors make biopics so generic they have little to say about the present or the past. Some films are iconic relics of their time because of the effects they used, the stars they championed and the look they adopted. Altman’s style was his own and it became the look of the ‘70s. His best films from this period seem to embrace their own influence and legacy and eventually even come to challenge it.

“MASH” so quickly became a hit and a staple for how storytelling and dialogue could be done that it looks less revolutionary compared to films he would release even a few years later. But Altman’s knack for transforming stories into his present day didn’t end at the war.

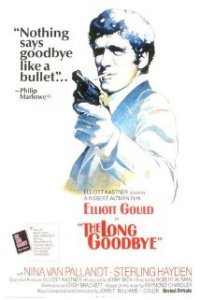

To adapt Raymond Chandler’s “The Long Goodbye,” Altman took the rugged Philip Marlowe of Old Hollywood and made him a chain-smoking, pitiful PI muttering one-liners under his breath. “Thieves Like Us” is dripping with period styling emblematic of the early 20th Century, but the film plays like an anti-“Bonnie and Clyde,” modern, scandalous and violent, but with a new self-aware mentality and style. In his Western classic “McCabe & Mrs. Miller”, the overlapping dialogue adds to the film’s rugged, observational quality and strengthens the sprawling cast of Western supporting players. And in Altman’s masterpiece “Nashville”, the drama is focused on just a few days in this American country town in the 1970s, but it feels like a portrait of the entire country writ large.

The universal nature of “Nashville” makes it a good place to start; nearly all of the players Altman amasses here will turn up across his other ‘70s pictures, and the storytelling and character arcs are all free-flowing, non-traditional and emblematic of Altman’s style across all his films. Roger Ebert wrote in his Great Movies piece that “Nashville” may not be about any one thing. It’s a tone poem and musical that moves from character to character, full of some of the same dry humor and busy sense of activity first seen in “MASH”.

It could be about nothing in particular, as Ebert says, specifically the idea that life is messy, always overlaps and never occurs in a straight line. But if it’s about anything, it’s Nashville itself. What makes it such a ‘70s movie is that everything Altman observes has a sense of irony and even an air of criticism to it. When the Coen Brothers spoke about making “Inside Llewyn Davis” and recording the song “Please, Mr. Kennedy,” they explained that it’s a joke song, but not a bad one.

In “Nashville”, the songs are a bit ironic, but they’re far from parodies. Haven Hamilton’s (Henry Gibson) opening number adorning the credits is a hollow political anthem befitting Hamilton’s garishly country attire, but you instantly know the song to be one of a famed veteran with a respect for the art. When Hamilton performs again later at the Grand Ole Opry, it’s a purely stylish, endearing and magnetic performance of a country classic. But Altman includes a sly wink when Hamilton is caught adjusting the microphone stand towering above him.

Even the sillier characters aren’t merely one-dimensional. Altman looks at them through two separate eyes and plays up their flaws and their finer points. Sueleen (Gwen Wells) is a cocktail waitress who can’t sing a lick, but aspires to be a singer. Her voice is its own punch line, but we’ve seen her ambition in her dressing room mirror, and pity her humiliation in a devastating striptease scene. Keith Carradine plays a womanizing jerk who calls up another girl in his black book as soon as he’s finished with Lily Tomlin. But he’s a guy with talent and charm all the same, and his performance of the Oscar winning song “I’m Easy” is another of the film’s high points.

A friend once commented about the show “Modern Family”, saying he loved the show because it has no “B-story”. All the plot threads matter equally and comprise the whole. “Nashville” works in that sense. Characters aren’t lead and supporting. They all have nuances, expressiveness and layers. And when they’re all together at the film’s closing political rally, it’s hard to imagine any film’s cast as rich and as sprawling as this.

Two years after “Nashville”, Altman made another contemporary drama, and while he retained the non-linear story, the observational character building and subtle nuance, he reduced the sprawling scope into something intimate and eerie. “3 Women” takes those big emotions and seems to magnify them in two peculiar characters, and never has Altman made a film as surreal.

It stars Shelley Duvall as Millie Lammoreaux and Sissy Spacek as Millie’s obsessive admirer and friend Pinkie. The two work at an old folks therapy home, and Millie is showing Pinkie the ropes. Spacek was no longer a teenager by the time she played Pinkie, but she still had that immature, girlish quality to her that makes her perfect casting as a lost deer in the headlights type. When Pinkie moves in with Millie and the two slowly become friends, it becomes increasingly clear what a blank slate Pinkie is. She doesn’t have other clothes, friends, a background or possessions. She’s creepy, clingy and desperate for Millie’s attention.

But Altman plays a little trick. The dialogue is still in his signature style, casual, overlapping and ordinary. He develops Millie as a perfectly normal individual chatting it up with friends and colleagues, going out to bars and shooting flirtatious smiles at her cute neighbor Tom. But slowly we pick up on the fact that Millie seems to be making small talk to no one in particular. She makes up conversation topics as she goes, seemingly talking through her colleagues and neighbors as though her presence doesn’t even register. “Don’t look now, but its Thoroughly Modern Millie,” one of her neighbors scoffs. Both Mille and Pinkie are equally bizarre empty shells, and what we know about these characters slowly erodes.

What’s so unique (it does however bare a lot of similarities to “Persona”) about “3 Women” is that Altman is now taking the tricks he has established throughout the ‘70s and using them to the point that nothing feels quite right. The dialogue is not just muted but it creates an awkward silence so thick you can cut it with a knife. He uses quick zooms and cold, distant characters that still have as many tiny intricacies as those in “Nashville” or “MASH”, but they’re packaged in a way that makes the movie beguiling and hypnotic instead of observational and inviting.

To be fair, that peculiar mood setting is not too far off from “MASH” in the first place. The TV show of the same name, which has become far more iconic over the years, is purely conventional and silly. While Altman stages sequences of zany anarchy that would rival and pay homage to the Marx Brothers, particularly the long football finale, so much of the film feels almost solemn and too quietly subtle in its humor, enough to make an unprepared fan of the show bristle.

That’s because while war was the setting in the TV show “MASH”, Altman makes it an actual background. We don’t see any images of war, but we see the aftermath Hawkeye and Trapper are stitching up. They mask their wartime stress behind deft double entendres and prank filled, stick-it-to-the-man attitudes that would become the decade’s hallmark. The audacity of some of these set pieces, like drugging an officer and photographing him with prostitutes as blackmail, removing a shower wall to publicly gawk at their naked female commander, or a football player touchily named “Spearchucker Jones”, all work because of how cavalier and coolly unaffected Donald Sutherland and Elliot Gould play Hawkeye and Trapper under Altman’s direction.

“MASH” also ends with a knowing wink to the time in which it belongs. The announcer on the PA reciting silly Old Hollywood films has now rattled off the cast and plot description to “MASH” as the film’s sly sign-off. Altman knows even at the breakout of his career where he stands and how his film belongs to both New Hollywood and Old.

Because of that fear of being lumped in too easily, his 1974 film “Thieves Like Us” has the gangster vibe of “Bonnie and Clyde,” the definitive New Hollywood movie, and makes a slower, more anti-climatic heist movie by design. The opening shot is a long, unbroken nature shot without the punchy editing reminiscent of the era. It fools our eye and delays introducing us to our real protagonists and point of focus. Once the thievery does begin, Altman keeps us outside the bank and away from the action. “I should’ve robbed people with my brain instead of my gun,” Keith Carradine’s Bowie says. The thieves then begin to lay low, and the romance between Bowie and Keechie comes not from a sense of excitement but almost from a lack of it.

Shelley Duvall shows up here as well, and across three of Altman’s films she is never cast the same. She was the obnoxious flirt in “Nashville” and the oblivious socialite in “3 Women”, and here she plays Keechie plain to fit the period simplicity Altman is aiming for.

Sadly, “Thieves Like Us” is not up to Altman’s same par as the other films included in this overview. His writing is ordinary and observational, but less layered and intricate. And despite a resistance to be “Bonnie and Clyde” during the rest of the film, that’s exactly how it ends.

But Altman’s films were made to be messy. That style defined his day, and he laid the groundwork for Paul Thomas Anderson and many more. At the end of “Nashville”, Altman has brought all his characters together, only for hell to finally break loose. It’s a powerful scene, in which everyone emerges in the heat of the moment and shows their true colors. Haven Hamilton takes the mic and proclaims, “You can’t do this to us in Nashville!” He rallies the crowd, and they blindly but nobly carry on the torch. Altman’s films in this time are like “Nashville’s” crowd, each so flawed, colorful and distinctive, that when brought together make up a universal whole.

For more, also check out previous writing on McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye, each masterpieces and certainly worthy of being called “essential” ‘70s Altman.

Critics who today bristle at true movie spectacles like “Avatar” or “Gravity” for want of a more substantive story are less likely to do the same when faced with a silent film. The technical precision and thoughtful filmmaking required to communicate ideas and tell any story seems to be enough.

Critics who today bristle at true movie spectacles like “Avatar” or “Gravity” for want of a more substantive story are less likely to do the same when faced with a silent film. The technical precision and thoughtful filmmaking required to communicate ideas and tell any story seems to be enough.

Released a year before “Chinatown”, Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” is the other dense masterpiece of mystery and contemporary noir with a plot so layered it may demand a second viewing to keep it all straight.

Released a year before “Chinatown”, Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” is the other dense masterpiece of mystery and contemporary noir with a plot so layered it may demand a second viewing to keep it all straight.